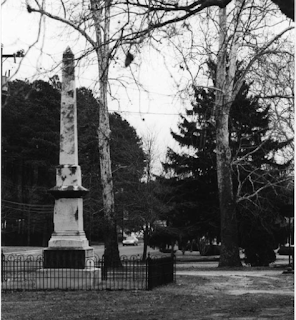

Confederate monument in Lancaster Court House, Virginia, from Gerald L. Cooper’s book,

"On Scholarship – From An Empty Room at Princeton.” —Photo by author.

As I was growing up in a simple house in the tiny town of Lancaster Court House, Virginia, from 1935 to 1950, I could not avoid a daily viewing of the Confederate monument across the road, a veritable landmark beside Virginia route 3. The monument stood tall in the midst of an iron-fenced enclosure, about forty yards west of my home, just across state-designated “Historyland Highway,” which links the Northern Neck’s historic sites — King Carter’s Christ Church, George Washington’s Wakefield and the Lees’ Stratford Hall — to Richmond, Fredericksburg, Alexandria and Washington.

In my pre-teen years, I did not spend my time contemplating that marble obelisk, but I knew it was there, looming as a great gray eminence even in bright sunshine. Eventually I gained an understanding of what it stood for, with the help of my schoolteacher mother. She also gave me an idea of what it didn’t represent—at least in our household. She had a friend over in Corrotoman who would genuflect before the monument, and any time she encountered a portrait of Robert E. Lee. (Corrotoman is also a peninsula derived from that river, which was named for the local Native American tribe; “cor-ro-toe'-man.")

“My dad’s from Neola, Iowa,” I used to say, when budding southern patriots at elementary school got me into a corner, defending their Confederate cause. My dad had died by the time I was ten, of a heart attack in 1945, so I had to find new ways to defend myself. That too was an early opportunity to be different.

My mother grew up in the lower Northern Neck — first Northumberland and then offshoot Lancaster County. She was a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC). One of her responsibilities as a member and recording secretary was placing small Confederate flags around the monument on Memorial Day or Decoration Day, as it was called in the 1940s. She had a supply of Confederate flags, each measuring about 15 x 15 inches, mounted on three-foot wooden, quarter-inch staffs. She would put the flags on display for the designated day each year by pushing the staffs into the ground at each corner of the monument’s enclosure, outside the surrounding iron fence.

More than once in my early years I absconded with a flag from Mom's storage closet to show off to a friend; I got caught, and was punished for the trespass. “The flags aren’t expensive or sacred,” my mom said, “but they are not playthings, and they belong to the UDC, not us.”

The Confederate monument had been erected in 1872 to honor the men of Lancaster who had died for the Southern cause. The Ladies Memorial Association of Lancaster County had raised funds for construction of the monument. The names of the 111 local men who gave their lives in the military service of the Confederate States of America (CSA) were engraved in the white marble that forms the upper section of the obelisk. These fallen warriors’ names were at first the only honorees on the monument.

In a pictorial history titled, "Virginia’s Historic Courthouses," I learned that Lancaster was the first county in Virginia to erect a Confederate monument after the war, and also the last county to complete a new courthouse, before the Civil War in 1861.

Not long after the monument was finished, the names of 346 survivors were also added to the memorial. Three bronze plaques at the base display the names of one hundred or so Lancaster County men who served in the Civil War and lived to come home—including my grandfather. These men were designated “Survivors of the War of 1861-1865” on the plaques. This statement conformed to the prevailing notion in the South that the term Civil War was unacceptable in describing the conflict.

Created by white Southerners to rationalize the South’s bitter defeat, the so-called “Lost Cause” movement reached its zenith in the 1870s. Lost cause advocates used such words as noble, righteous, and chivalrous to describe aspects of the Confederacy in the hope of eradicating the pain of defeat and the ignominy of Reconstruction.

Thus the Confederate monument’s revisionist symbolism in history became a fact of life in Lancaster County by the time I was born, in 1935 — just 70 years after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in 1865.

[Editor's note: In May, 2017 I have revised this article slightly and have presented it here again, in view of the recent renewal of interest in Confederate monuments and other icons of the Civil War.]